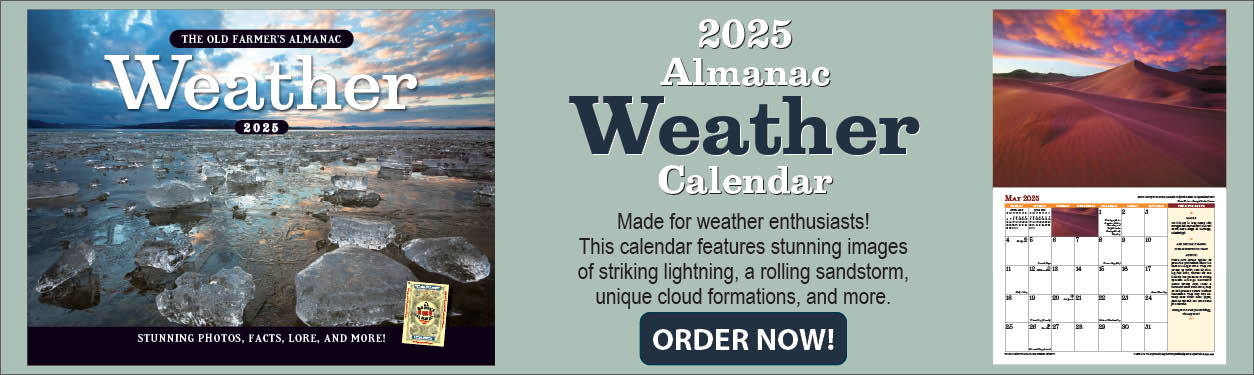

If you’ve ever been close to a lightning strike, you know just how powerful a stroke of lightning is.

With temperatures five times hotter than the surface of the Sun and enough electricity to briefly power a city, one of Zeus’s thunderous bolts is clearly something beneath which you don’t want to find yourself.

- Surprisingly, only about 10 to 20 percent of all lightning within a storm is the lightning that we see. In fact, the vast majority occurs within the storm cloud rather than between the cloud and the ground.

.JPG)

Above photos show lightning during a severe thunderstorm over Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on June 24, 2013. Credit: Matthew Cappucci.

Lightning is Mother Nature’s natural balancing act between charged objects. In this case, friction between raindrops, ice crystals, and other cloud-borne particles results in a negative charge building up within the base of the cloud as “outer-shell” electrons find their way to this region. As the charge grows in the cloud, it begins to become nearly too much for the cloud to handle; a bolt of lightning flashes between the cloud—negative—and the ground—positive by comparison—as a means to equalize and balance the opposite charges.

Every time lightning strikes, hundreds of millions of volts (a measure of the difference in charges between two objects) and nearly 20,000 amperes (a measure of the quantity of current flowing through a lightning bolt, exerting energy dependent on the voltage) course through the pulsating vein of power.

The “flickering” appearance of lighting is due in part to the sheer quantity of raw power being exerted through it; so much electricity passes through a bolt of lightning that multiple “trips” are required in order for all of this power to be exchanged successfully.

An instance of ground-to-cloud, or “upward” lightning during a severe thunderstorm over Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on June 24, 2013. Credit: Matthew Cappucci.

- A common misconception of lightning is that it travels downward from the base of a cloud, with its force being recognized once it reaches the ground. In reality, however, such is not the case. It travels both ways. The downward-reaching branch is met by an skyward-bound “upward streamer.” Once these two segments of the bolt meet, a path has been formed for the incredible power of a lightning strike to be achieved. It can be thought of in essence as a microcosm of the Transcontinental Railroad: Crews from both coasts worked in building track to eventually meet in the middle, at which point thousands of passengers were able to move across the length of track spanning the nation. In this way, a lightning bolt is analogous to a “railroad for electrons.”

Lightning during a severe thunderstorm over Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on September 1, 2013. Credit: Matthew Cappucci.

But not all lightning bolts are quite as simple; oftentimes, one lightning bolt can trigger a series of consequent electrical disturbances that ripple across all levels of the atmosphere.

- “Superbolts,” which seem a myth coming from ancient folklore and legends, are a legitimate phenomenon regarded as one of the most dangerous types of all lightning. A “superbolt” describes an extreme bolt of electricity emanating from the positively charged top of the cloud, harnessing three to as much as 100 times the power of an ordinary lightning bolt.

What makes these bolts so dangerous, however, is their tendency to strike upward of 10 miles away from a thunderstorm. These so-called “bolts from the blue” have been known to strike on perfectly sunny days featuring crystal-clear skies, with little more than the barely audible rumble from a distant thunderhead. The power of these bolts has sparked dozens of forest fires that oftentimes remain unextinguished by rains that fall too far away to be of any assistance. Superbolts are known for their remarkable power. It should come as no surprise that a superbolt once threw a 600-pound church belfry several hundred yards in Michigan. While statistically less than one out of every 100,000 lightning strikes is from a “superbolt,” their effects can be startling.

On May 21, 2012, residents of Tulsa, Oklahoma, awoke to about 15 seconds of earthquake-like shaking, intense thunder, and resounding booms shortly after 3:30 A.M. The National Weather Service later identified the culprit as a “superbolt,” which created what some referred to as a “thunderquake” strong enough to set off car alarms within a half-mile radius of the location of the strike. One eyewitness told local news media that their bed was shifted 4 feet due to the shaking associated with the bolt.

A red sprite photographed above a severe thunderstorm by NASA scientists aboard the International Space Station.

- The same storms that produce superbolts frequently have enough energy to produce other types of lightning as well; red sprites and blue jets both form in the region miles above a severe thunderstorm, close to space, while ball lightning is regarded by scientists as one of the most curious forms of lightning to date.

A ‘giant blue jet’ captured by Thijs Bors in Australia’s Northern Territory during a vigorous thunderstorm.

One of the only known photographs of ball lightning in existence, snapped in Nagono, Japan in 1988; photographer unknown.

So, the next time you find yourself faced by a thunderstorm, perhaps take a moment to watch the show; after all, it’s like Mother Nature’s way of treating us to her own Independence Day fireworks display.

Authored by Matthew Cappucci.

.JPG)