Caption

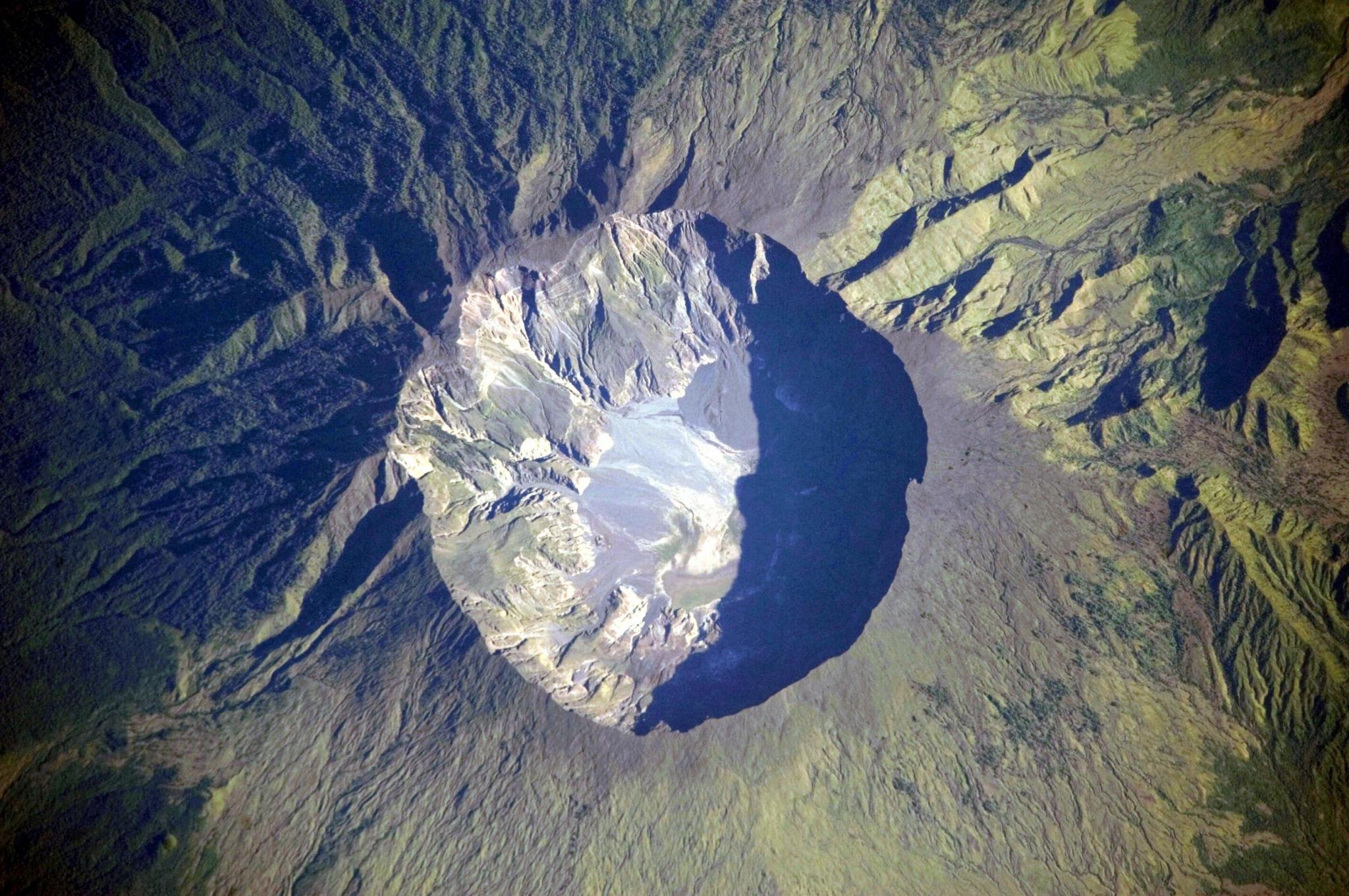

The dust from the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) caused a worldwide lowering of temperatures during the summer of 1816, when the Almanac, legend has it, inadvertently but correctly predicted snow for July.

Photo Credit

Culver Pictures

Subhead

Largest eruption in recorded history led to global temperature drop

I loved reading this gave me more insight on this GSM that we are heading into the library in my hometown has this book going to check it out.

The 2018 question - What impact will the volcanic eruptions in Hawaii and Guatemala have on the weather patterns?

I really enjoyed reading this. It's a part of history I have never heard before. I'm going to see if the dates match up to when some of my ancestors moved at that time. Very interesting.

Here we are almost to April 2017, but still no warm temperatures that you enjoy in Spring (60°F, or above), is still not in sight. We still have these same temperatures, you typically get in December, January, or February, which is way below that (difference of 10°, 20°, or even 40° below normal). There is still no sign of that in late February, or early part of March this year, that this a time when Spring should arrive. The cold arctic air where we get that cold wintery weather from takes away that warm air that we need for Spring, and it even wipes it out.

The government should do something soon in the future, so people can enjoy those spring or Summer temperatures, by reducing global warming, or global cooling that is causing these everlasting winter seasons, by creating artifical sea ice in the Arctic, that could produce these warmer temperatures that people enjoy during Spring or Summer, to protect people who live in the Northeastern U.S. from these snowstorms, where they mostly occur during occur.

He, according to an apocryphal story that goes back to as early as 1846, had predicted for July 13, 1816, “Rain, Hail, and Snow”—all three of which, greatly to his amazement, did fall on this day....I guess this should have read 1746?

Hello,

Just wanted you to know how much I enjoy your information.

Thank you!

Comments