What’s your best knife? Whether you’re slicing through a tomato, a potato, or a T-bone, good knives are the most important tool in the kitchen. A good knife will last through the next generation with proper care. See our tips on choosing a great knife.

The Chef’s Knife

Let’s focus on the chef’s knife: this is the kitchen workhorse that does 90 percent of our mincing, dicing, slicing, trimming, and chopping. Because the chef’s knife’s 8–10-inch blade comes into repeated, sometimes vigorous contact with the cutting surface, it should be designed to withstand these impacts.

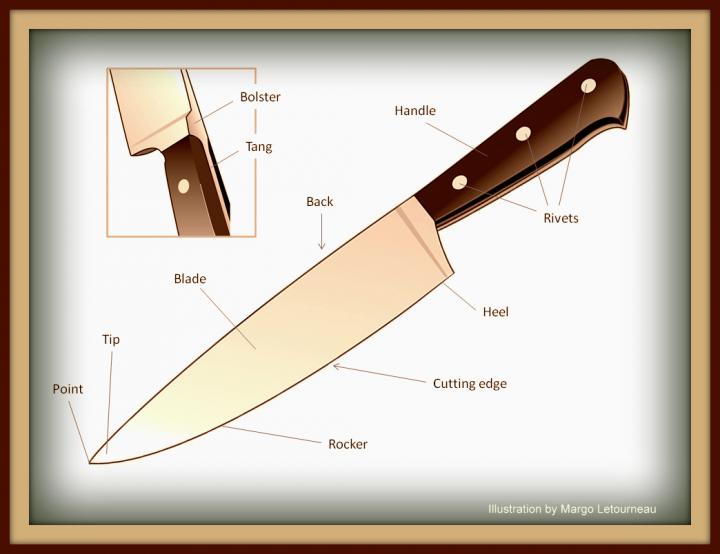

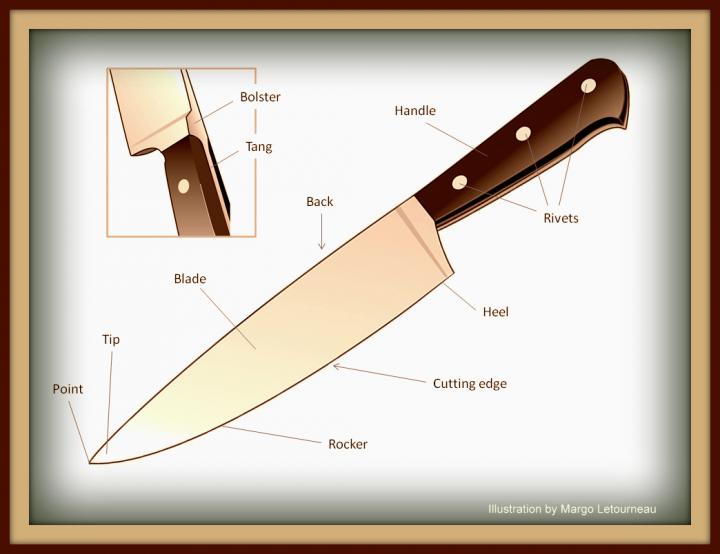

We’ll start at the bolster, the thickened part of the blade that leads into the handle. The bolster is the balance point on most chefs’ knives. It adds necessary weight to the knife, but more to the point, it serves as a cushion between your fingers and the blade. Without a blunted bolster, either your second or third finger—depending on the grip you use—could easily become chafed by rubbing against the rear of the blade. German knives tend to have a thicker bolster, which makes them heavier for the rocking motion. Less bolster means a lighter knife geared more to a comfortable slicing motion.

The top edge of the blade is simply known as the back. Some knives—serrated ones, for instance—have a narrow back; they’re effective for fine, thin slicing. But on a good chef’s knife, the back is wider and flat—the better to push on with your free hand when you need extra thrust or stability.

The back of the blade extends to the tip, which in turn curves around to the bottom of the bolster. This entire bottom stretch—from tip to bolster—is called the cutting edge. It is the business side of your chef’s knife.

The tip is the narrowest part of the cutting edge and includes the point and the first several inches of the cutting edge. A perceptive cook learns that the tip is essentially a knife within a knife, a fine-cutting tool for thin-slicing mushrooms, scallions, cherry tomatoes, etc. The tip is also the most vulnerable part of the knife; it should never be used as a can opener or prying tool, and it can break if it falls to the floor.

When we cut with a chef’s knife, we often use a rocking motion due to the curved part of the cutting edge known as the rocker. That’s where most of the blade’s taper is. Behind the rocker is the heel, the thickest part of the cutting edge. You’d rely on the rocker to mince your way through a pile of parsley, whereas you’d bear down on the heel, with your free palm pushing down on the back, to halve a hefty winter squash (perhaps, for safety, first piercing the skin with the point to get the blade started).

The Tang

The blade extension sandwiched inside the handle is called the tang. Traditionally, the best knives have had what’s known as a full tang—one that’s the same size and shape as the handle and whose sandwiched edge is visible all around the handle. Today, there’s a trend away from full-tang knives as manufacturers find new, less expensive ways to bond partial tangs to handles.

I have at least one good knife with no visible tang. The handle pieces are made just slightly larger than the tang itself and then heat-shrunk right onto the tang, an arrangement that’s guaranteed for life and has held up well for 10 years now.

Knife Handle

As far as handles go, wood looks nice, but it isn’t the best material for knife handles. After repeated washing and drying (causing the wood to swell and shrink), the rivets may eventually work their way loose and shorten the life of your knife. The best kitchen knives have handles made of high-impact plastic, such as polypropylene or fiberglass nylon.

Only buy a knife that fits your hand comfortably and that you’ll be able to grip securely even if your palm sweats. If you tap the blade against a cutting board, the knife shouldn’t feel heavy but rather vibrate back in your hand. You want to feel a connection with the knife so you have control over it.

Blade Material

Consider the steel used in the blade. Carbon steel takes an edge nicely but dulls quickly; stainless steel won’t rust, but you can’t sharpen it. High-carbon stainless steel is an alloy that combines the best properties of both; it’s easy to sharpen, keeps the edge for a reasonable period of time, and won’t rust. With the exception of serrated knives, which as a rule can’t be sharpened, high-carbon stainless steel is far and away the best kind of blade to consider.

Blade Shape

The heavier, German-style knives have a thicker blade and a thicker bolster that’s more conducive to a rocking motion. Because of their thickness, they also tend to chip less and last longer. French- and Japanese-style knives have a lighter, thinner blade more geared to more precise slicing and maneuverability. It depends on your preference. Try slicing potatoes or onions and see which feels better to your hand. Also, try cutting through herbs and make sure your knife doesn’t crush them.

Complete Set of Knives

Think twice before buying a complete set of kitchen knives; the chef’s knife might fit you like a charm, but the parer might be too small. If you can see the rivets, are they flush to the handle? If they aren’t and protrude even slightly, they’ll irritate your chopping hand.

Tips for Storing and Cleaning Knives

In order to last, good knives need to be protected. A heavy (stable) freestanding knife block or one designed to fit in a drawer is a great storage option if it has enough slots and is near your work area.

Also, clean knives immediately after each use, and don’t let food harden on them. Once you’ve washed them, dry your knives right away; with the blade pointing away from you, drape a towel over the back of the knife and gently swipe the blade clean from bolster to point. Store them at once.

Good knives that are properly cared for can be invaluable kitchen helpers for generations to come.

For more about knives, see “Which Knife to Use, How to Sharpen Knives, and Safe Cutting Techniques.”

Comments