Caption

John Withee with his bean case in 1981

Photo Credit

Seed Savers Exchange

Subhead

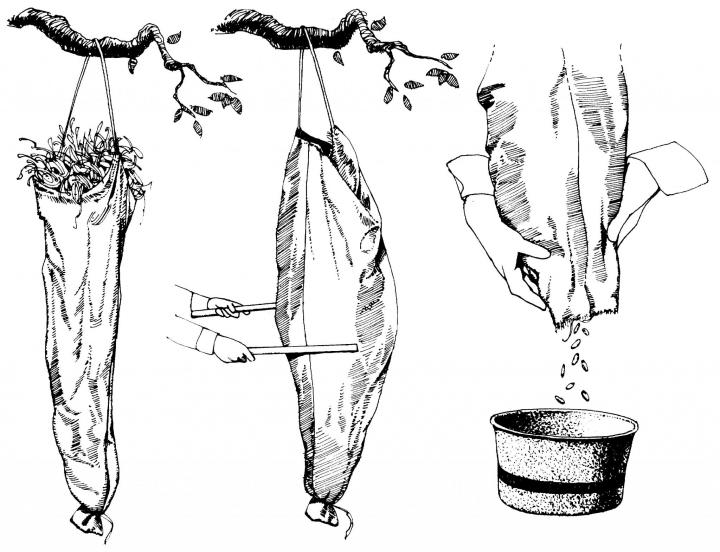

The simplest solution for threshing dry beans.

More Like This

Bean Protein: There are three types of Protein; "Dairy fish Eggs and meat have first class protein; Beans have 2nd class protein; fruits and vegetables have third class Protein; Beans have higher protein because their roots have a macrobacteria which uptakes nutrients;better;

Comments