Even though many seed companies have gone digital, I’m amazed at how many catalogs we still receive in the mail. If you think there are too many seed catalogs now, back in the late 1880s there were thousands of small seed companies. Although the cultural information and descriptions in old catalogs are helpful if you are researching heirloom plants, the artwork is the draw.

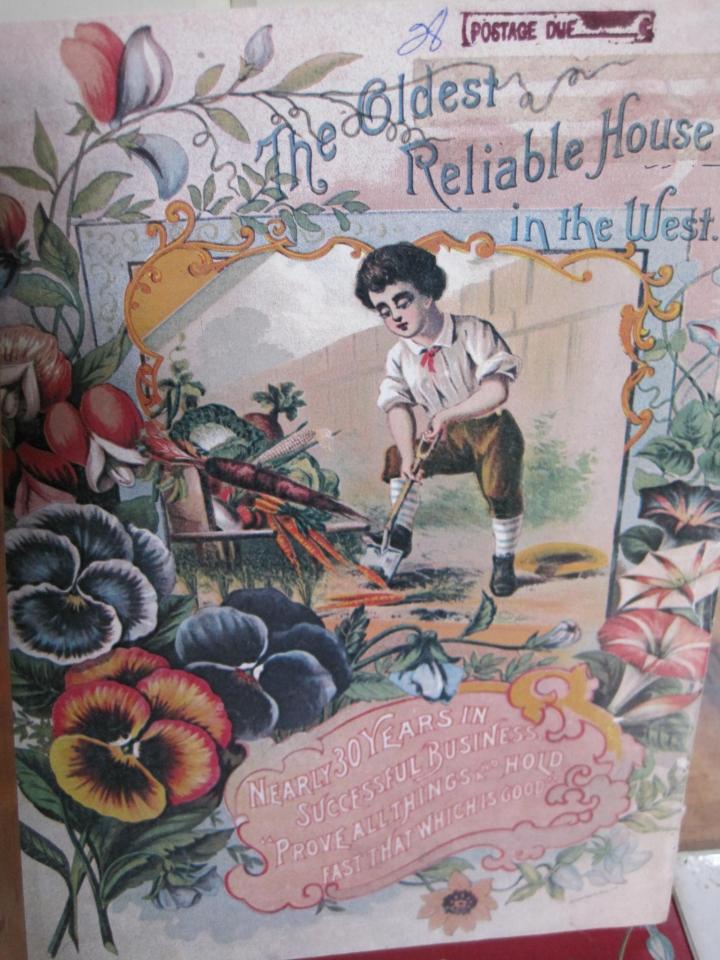

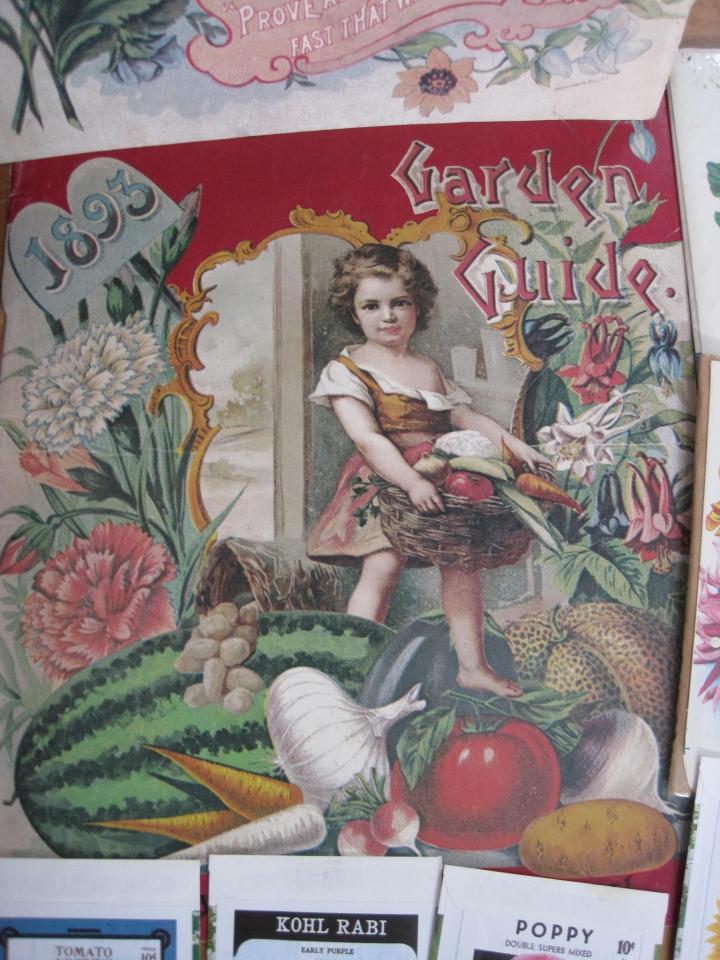

Many of the pictures in the old-fashioned catalogs and on the seed packets themselves were hand painted from nature. Later they were lithographed using images stippled onto slabs of limestone. Each color had its own slab and the combined printing gave a 3D effect. The pictures in these antique catalogs and on the seed packets are now a highly collectible artform. I can only imagine that in their day they were as enticing as our richly illustrated catalogs are today.

It was through my interest in old-fashioned catalogs that I discovered Carrie H. Lippincott, the pioneer seedswoman of America. (At least, that was the title she chose to give herself.) She started a seed business in Minneapolis in 1886 out of necessity, to increase the family income. She mailed her first catalog in 1891 and received 6,000 orders. By 1896 she was getting over 150,000 orders per year! A publication of her day is quoted as saying that the key to her success is prompt service, the best seeds, reasonable prices, and beautiful flowers—all done by a woman.

Carrie had a shrewd sense of marketing. She dealt exclusively in flower seeds and targeted her catalog to appeal to other women.

Her colorful 5”X7” catalog looked more like a greeting card with most of the lithographs showing women and children surrounded by beautiful flowers. She referred to each year’s catalog as her annual “greetings” and updated customers on her family and her products in a chatty, personal way. In 1898, Lippincott mailed 250,000 catalogs; 1 in 60 households in the nation were on her list. Working with her mother and her sister, she created a thriving business based on hard work and hands-on gardening experience.

Naturally others made note of her success and this led 2 male-owned companies in Minneapolis to begin marketing their seeds under women’s names. In her 1899 catalog, Lippincott wrote,”It is a peculiar thing in this day and age that a man should want to masquerade in woman’s clothing. I do not advise a life of business for any woman when it can be avoided. It means self-sacrifice.”

One of Lippincott’s competitors was Jessie R. Prior. Her company ran under her husband’s name for the first 5 years until they realized it would have more appeal if they used Jessie’s name instead. By 1905 she built up a business that occupied an entire block of 3rd Avenue South in Minneapolis. Jessie claimed to have the only seed testing grounds in the West, located on the shore of Lake Minnetonka. But her success was brief and by 1907 the Jessie R. Prior Flower Company had disappeared.

Emma White was another seedswoman of Minneapolis. To quell rumors that she was a fake she wrote in her catalog, “I am a real live woman and I give personal attention to my business.” A knowledgeable plantswoman, Emma was active in the Minneapolis Horticultural Society and president of the Women’s Auxiliary in 1903. She published her first catalog in 1896 and rode on Lippincott’s wave of success for years.

If you are interested in owning reproductions of antique catalog artwork, reprints are available from many sources online otherwise keep poking around second-hand stores and yard sales and you just might find some originals!

Also, see the Almanac’s list of modern day garden seed catalogs and Web sites here.

Comments