Spring is here, and this means that plant sales will be happening soon. In many states, we now need to be careful about what might be lurking in the soil in which those plants arrive. Look out for Asian “jumping worms.” Learn more about identifying and preventing these highly invasive worms.

You may have heard about jumping worms, also called snake worms or crazy worms for the way they writhe when you try to pick one up. An invasive worm that came here from Japan and Korea, it is now found from Texas to southern Canada.

Unlike other earthworms that burrow deep into the soil, jumping worms live in the top 3 inches of soil and in leaf litter and mulch. They are fast growers and voracious eaters, consuming all the organic matter in the topsoil, depleting it of nutrients and making it hard for other soil-dwellers to compete.

Identifying the Jumping Worm

Though it is similar in size it looks different from a nightcrawler. The clitellum or band on a jumping worm is white or gray, flat, completely encircles its body, and is located near its head. On a nightcrawler, the band is red or pink, raised, does not go all the way around the worm, and is more toward the middle of its body.

I caught these slow-movers on a cold September morning so they didn’t put up much of a fight.

Note how near the clitellum is to the head.

If your topsoil looks like coffee grounds (loose and granular), you probably have jumping worms. The grainy dry pellets act like a quick-release fertilizer but those nutrients are gone after a rainstorm, washed away too fast for plants to absorb them.

If your garden topsoil starts to look like coffee grounds, you probably have jumping worms at work.

Why Jumping Worms Are Destructive

Jumping worms not only deplete the topsoil of nutrients and moisture but also affect soil chemistry, making it hard for some seeds to germinate and for seedlings to grow. This greatly alters habitats, especially in forests that rely on a layer of leaf litter to supply nutrients to trees and support new growth. It also has an effect on your garden. Their castings, which in regular earthworms are an asset, alter the structure of your soil and affect root growth, making it difficult for seedlings to get established and for perennials to store enough nutrition to survive over the winter.

Jumping worms don’t eat your plants, but they will eat all the available decaying organic matter, including any mulch you spread. They may also be present in your compost if the pile doesn’t reach 104 degrees for 3 days or more—the temperature necessary to kill not only the worms but their eggs.

Life Cycle of a Jumping Worm

Jumping worms die off as soon as the weather gets cold, but they are self-fertile and can reproduce without mating. All it takes is one worm to start a population explosion. They leave behind tiny, brown, egg-filled cocoons that winter over and hatch out in the spring.

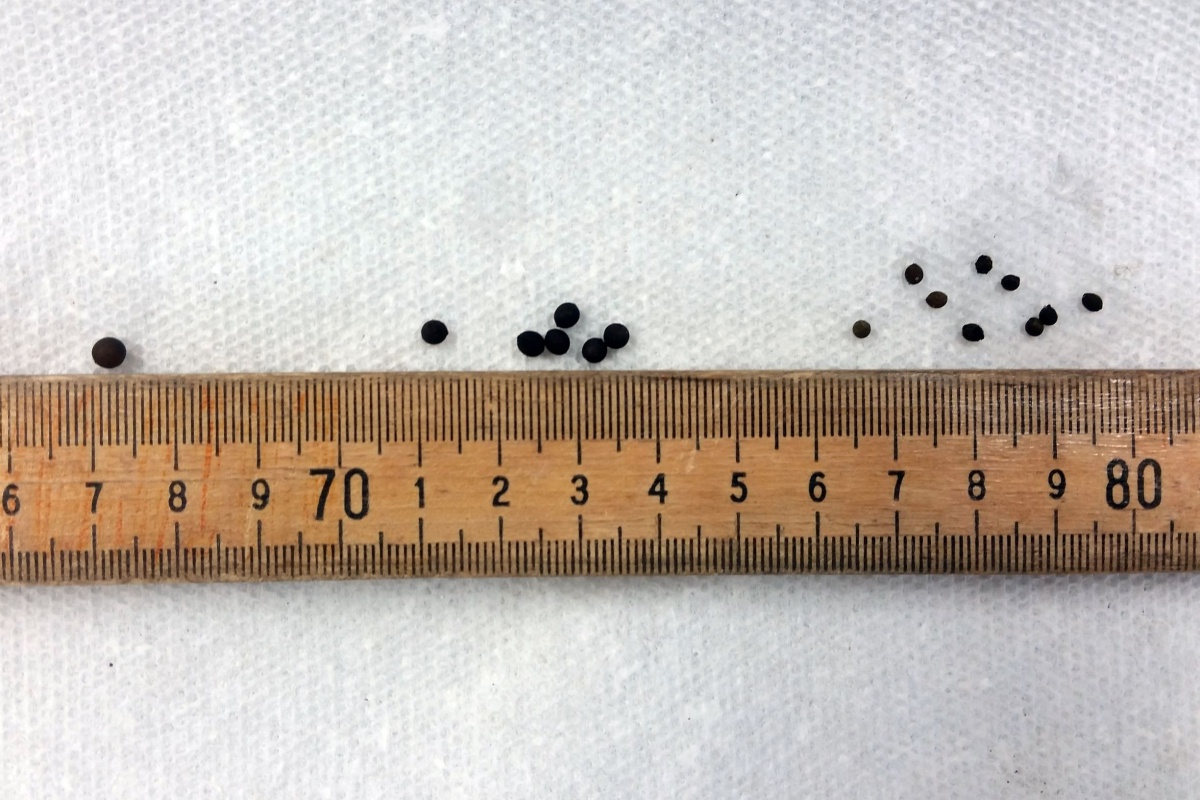

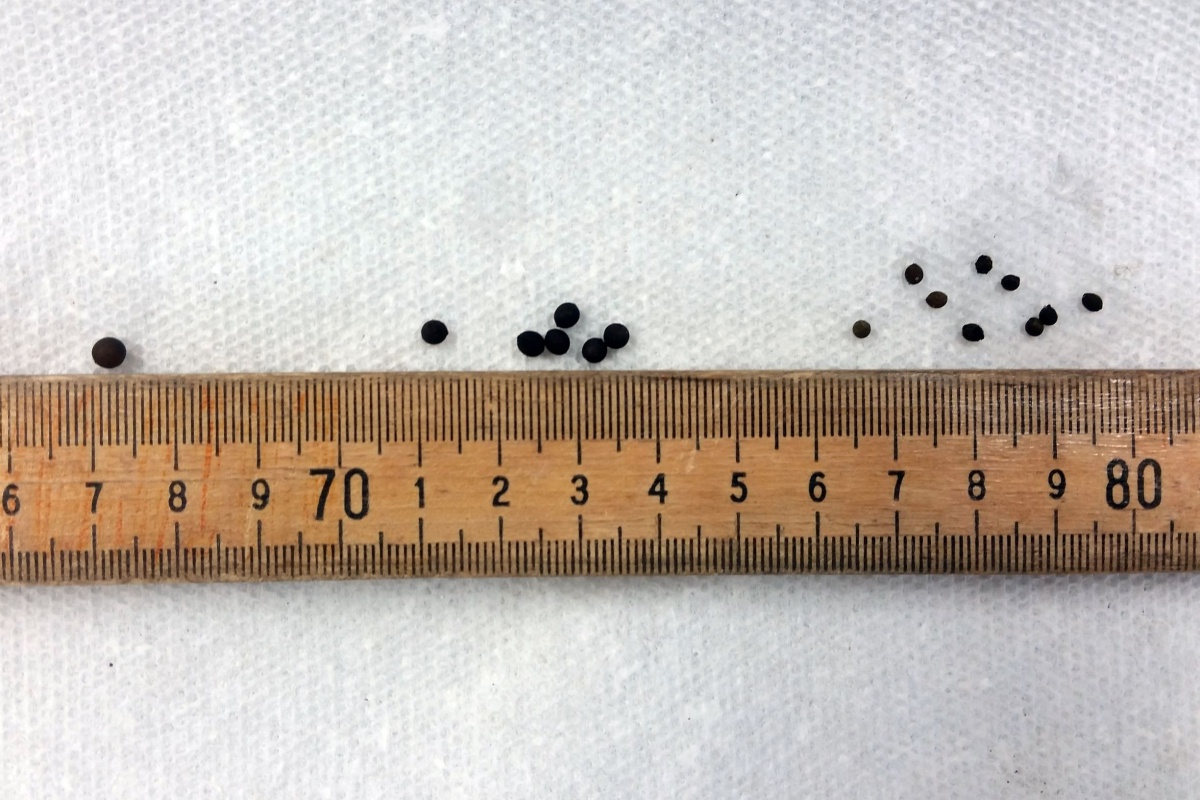

Jumping worm cocoons are tiny! Photo courtesy of Marie Johnston - University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum.

The cocoons are hard to spot since they are about the size of a poppy seed and blend in with the soil. They also are resistant to cold and drought. After hatching, the small worms spend the summer eating and growing. Look for large worms in June and July. They lay cocoons from August to September, and the first freeze kills the adults. Depending on your location, it takes between 60 to 90 days from hatching to reproducing, so most parts of the US have only one generation a year, but some places can have two or more. Eggs are viable for two years.

How to Get Rid of Jumping Worms

Pass the mustard! Seriously, to see if you have jumping worms in your garden, try this simple mustard test. Mix 1/3 cup of ground mustard seed with 1 gallon of water. Pour it slowly over a patch of bare soil. The mustard irritates their skin, and they will come to the surface where you can count them … or catch them if you are fast! You can also use the mustard test on a potted plant to see if it has any adult worms in it. According to Cornell University, this concoction is safe for most plants, but it doesn’t kill the worms, so you have to physically remove them.

Once you have established that you have jumping worms in your garden, to lessen the population, catch and dispatch as many of the adults as you can get hold of before they lay eggs for next year. Heat kills them so putting them in a plastic bag to cook in the sun for at least 10 minutes works fast. Cold does them in as well so you can put them in the freezer (just don’t forget they are in there!) You can also drown them in rubbing alcohol or vinegar.

So far there are no proven remedies. Abrasives such as bio-char and diatomaceous earth are being studied as ways to deter or even kill the adults. Plants that are high in toxic saponins are being analyzed for use as natural deterrents. Solarizing affected soil by covering it with clear plastic to reach temperatures high enough to kill the adults and the eggs is also being researched.

Where Are Jumping Worms?

As of 2021, these invasive worms can be found in over a dozen states: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin.

So, back to the plant sales! If you are participating, you should wash the roots of any plant you dig up to remove the cocoons, then pot the plant in a disinfected container with new store-bought potting soil. When washing the roots, be sure to capture the water and soil in a tub. You can either let the water evaporate and then pour boiling water over the soil to kill the cocoons or strain the solids out and put them in a bag to cook in the sun to kill any eggs.

Beware of any plant you purchase or receive as a gift. It could be a Trojan horse full of jumping worm eggs ready to hatch!

Now learn about the “good guys” and how to attract earthworms to your garden!

Comments