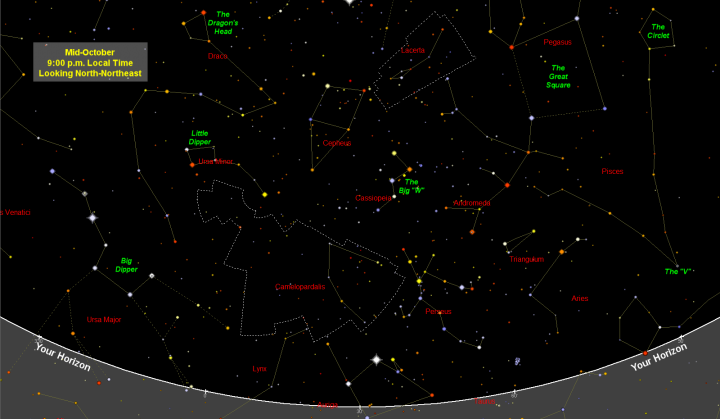

Welcome to the October Sky Map! This month, we highlight constellations. Who was the first person to record constellations? How many constellations are there? Are the constellations permanent? Let’s go stargazing—with our complimentary and printable map of the night stars.

Just click here or on the image below to open the printable map—then bring outside!

How Did Constellations Come to Be?

As human beings, it is in our nature to seek order from chaos, to find patterns even where none exist. It’s no surprise, then, that no matter how far back we look into recorded history, we find ancient peoples drawing sky maps and inventing names for what they observed.

Inevitably, ancient observers of the sky saw patterns in the stars—animals, characters—patterns that we now call “constellations.” Beginning at least 7,000 years ago, early astronomers were documenting mythological creatures, supernatural beings—even ordinary tools and weapons—all composed of stars. You’ll recognize so many of the names and shapes:

- Orion (the hunter)

- Canis Major (the greater dog)

- Cassiopeia (the queen)

Over time, the names and even patterns of most constellations have changed as different cultures have applied their own mythology to the night sky.

In fact, the 88 constellations that we recognize today were not agreed upon until the 20th century.

Constellations, Then and Now

THEN: Originally 48 Constellations

For most of recorded history, only the brightest or most distinctive star patterns were recognized as constellations. For millennia, some parts of the sky belonged to no constellation at all. This was still the case in the 2nd century when Greek-Roman astronomer Claudius Ptolemy produced one of history’s most important scientific writings, the Almagest. This colossal work comprised 13 books, each devoted to a different aspect of astronomy. Books VII and VIII concerned the stars and identified 48 constellations.

Over the next many centuries, astronomers slowly invented additional constellations from stars that Ptolemy had failed to include in his original 48.

This month’s sky map shows two of them.

- In 1612, Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius created the constellation Camelopardalis, the Giraffe, from a jumble of faint stars between Ursa Major and Perseus.

- The constellation Lacerta, the Lizard, was invented in 1690 by Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius from otherwise unassigned stars between Cepheus and Pegasus. A prolific constellation inventor, Hevelius created seven new constellations where none had existed before.

The star pattern of Camelopardalis looks nothing like its namesake, but the stars of Lacerta can at least be imagined as a reptile of some sort.

Throughout the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, new constellations were gradually invented to fill in those parts of the sky that had none. Occasionally, there were conflicts, such as when Edmund Halley (of Halley’s Comet fame) proposed a new constellation to honor King Charles II of England. Other astronomers rejected the idea of naming constellations for contemporary persons, so Charles’s constellation never came to be.

NOW: The Official 88 Constellations

The haphazard nature of constellations was on the agenda of the newly formed International Astronomical Union (IAU) at its first General Assembly in 1922. The assembled delegates decided that the sky would be divided into exactly 88 constellations and that their boundaries would be drawn so that every part of the sky lay within a constellation. No more unassigned stars!

All but one of Ptolemy’s ancient 48 constellations made the IAU’s modern list of 88. Because every point on the sky must lie within a constellation, the boundaries of some constellations resemble a gerrymandered Congressional district. Note the very convoluted outline of Camelopardalis on our sky map. The 88 IAU constellations are still in use today.

The items highlighted in green on our sky map are known as “asterisms.” These are distinctive (but unofficial) star patterns that lie within constellations. When getting your bearings under the stars, it’s often easiest to first spot an asterism and then use it as a guide to finding the parent constellation.

October Sky Map

Click here or on map below to enlarge (PDF).

Sky map produced using Chris Marriott’s Skymap Pro

How to Read the Sky Map

Our sky map does not show the entire sky which would be almost impossible. Instead, the monthly map focuses on a particular region of the sky where something interesting is happening that month. The legend on the map always tells you which direction you should facing, based on midnight viewing. For example, if the map legend says “Looking Southeast,” you should face southeast when using the map.

The map is accurate for any location at a so-called “mid northern” latitude. That includes anywhere in the 48 U.S. states, southern Canada, central and southern Europe, central Asia, and Japan. If you are located substantially north of these areas, objects on our map will appear lower in your sky, and some objects near the horizon will not be visible at all. If you are substantially south of these areas, everything on our map will appear higher in your sky.

The items labeled in green on the sky map are known as asterisms. These are distinctive star patterns that lie within constellations. When getting your bearings under the stars, it’s often easiest to spot an asterism and use it as a guide to finding the parent constellation.

The numbers along the white “Your Horizon” curve at the bottom of the map are compass points, shown on degrees. As you turn your head from side to side, you will be looking in the compass direction indicated by those numbers. The horizon line is curved in order to preserve the geometry of objects in the sky. If we made the horizon line straight, the geometry of objects in the sky would be distorted.

Comments